How I Grew To Love The Outdoors

January 19, 2020 - 6 minutes readThis post is the first in a series on our School Goal for 2019-2022.

How I Grew To Love The Outdoors, by Grade One Teacher Shelley Morton

I often wonder how I became an advocate for place-based learning. I don’t camp; I book vacations at The Four Seasons. Wilderness Wednesday was a good excuse to buy Hunter boots. Yet, when our curriculum shifted in 2015, we suddenly had permission to do many things. Personal responsibility, creative thinking and play were as, if not more, important than what facts students had to learn. Children were envisioned as “co-constructors of knowledge…engaging with people, places, objects, and ideas” (Play Today Handbook, 2019). I felt the freedom to spend an entire afternoon outside, learning playfully. Our forays led to memories; throwing snow on the winter solstice, catching a real live frog and discovering the meadow full of frosted webs one Fall morning. I never saw any of this until the children showed me. What I have learned from two and a half years out in the forest is what it feels like sometimes outdoors. We thrive given that freedom to run, roll, forge streams, laugh loudly, and connect. We simply get very different ideas when we think about things in special places.

Making Meadow Memories, December 2017

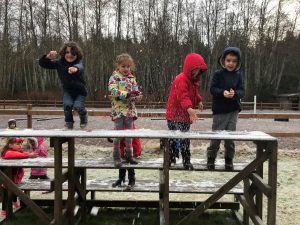

A favourite Kindergarten and Grade 1 memory was throwing snow at the teacher!

Pond Explorers, April 2019

A peak moment, in which I caught a frog together with my Grade 1 students.

Developing Theories, March 2019

A Kindergarten student developed a theory over a year in the forest, that plants need other plants to care for them.

Every three years, we as a school community write a Framework for Enhancing Student Learning. We set our school goals and develop a plan to help students be successful. We examine and debate data seemingly endlessly. What the data told us, as a Bowen Island Undercurrent article of December 5th recently revealed, is that a quarter of the children here on Bowen Island are vulnerable, meaning that “without additional support and care, [they] are more likely to experience challenges in their school years and beyond” (“Local Committee Advocates for Island’s Children”, Bowen Island Undercurrent, 2019). Further, when a recent Ministry of Education survey asked students, “Do you like school?”, our students responded that they liked school slightly less than the district average. While we are proud of our students’ work in literacy and numeracy, it is clear that we as educators have work to do. With much on our minds, we wondered how engaging students in place-based learning will enhance students’ well-being, deepen their engagement and ability to reflect on their own learning, and further their care for others and the communities to which they belong.

Place-based learning seems to mean more than going outdoors; indeed, broadening and deepening our understanding of the approach is part of our task. One respected school defines place-based learning as “an approach that connects learners and communities to increase student engagement, boost learning outcomes (and) impact communities” (one can read the full introduction from Teton Science Schools here). The Centre for Ecoliteracy identifies natural processes that are critical for children to learn about; among them continual cycles, dynamic balance which allows us to thrive together, and networks of relationship and the idea that we depend on our connectedness. I know the importance of unstructured outdoor play – how it promotes joy, competence, resiliency, and helps to maintain healthy relationships – which is echoed by leaders in our field, including the Canadian Public Health Association. This approach is ambitious and energizing. I feel positive and proud when doing this work.

We are hopeful that many of you will join us and support our place-based journey. Ask questions. Project enthusiasm. Provide gear. I would personally suggest that if you haven’t watched CBC’s documentary “The Power Of Play”, do, and provide time and psychological space for your children to play outdoors. As teachers, we really don’t get anywhere without your support, and my colleagues and I are always so grateful for it.

0 Comments